CHUCK BERRY

Chuck Berry is known the world over as the Father of Rock and Roll, and rightly so. It was he who married country music to the blues, wrote poetic lyrics that lit the imagination, sang them over motorvatin’ rhythms and played clarion riffs that established the guitar as rock and roll’s iconic instrument.

With indelible hits such as “Johnny B. Goode,” “Maybelline,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and so many others, Berry’s music became the lingua franca of rock and roll. Somewhere in the world right now, it’s pouring out of a radio and someone is playing it onstage.

Meanwhile, out among the stars, “Johnny B. Goode” is representing to the universe the best of what humanity has to offer. The song is etched into the grooves of the golden record attached to the Voyager 1 space probe.

Berry was the first member inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He’s a member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame, a recipient of a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and a Kennedy Center Honor. No less an authority than John Lennon declared that Berry’s name was synonymous with rock and roll itself. Bob Dylan called Berry the “Shakespeare of rock and roll.”

But you already knew all that.

In his hometown of St. Louis, Berry is known as the native son who became world famous but never left home. Throughout his long life, Berry maintained residences in St. Louis and in nearby Wentzville, Missouri, never forgetting that it was in the St. Louis-area clubs – and especially just across the Mississippi River at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, Illinois – where people first took notice of that brown-eyed handsome man.

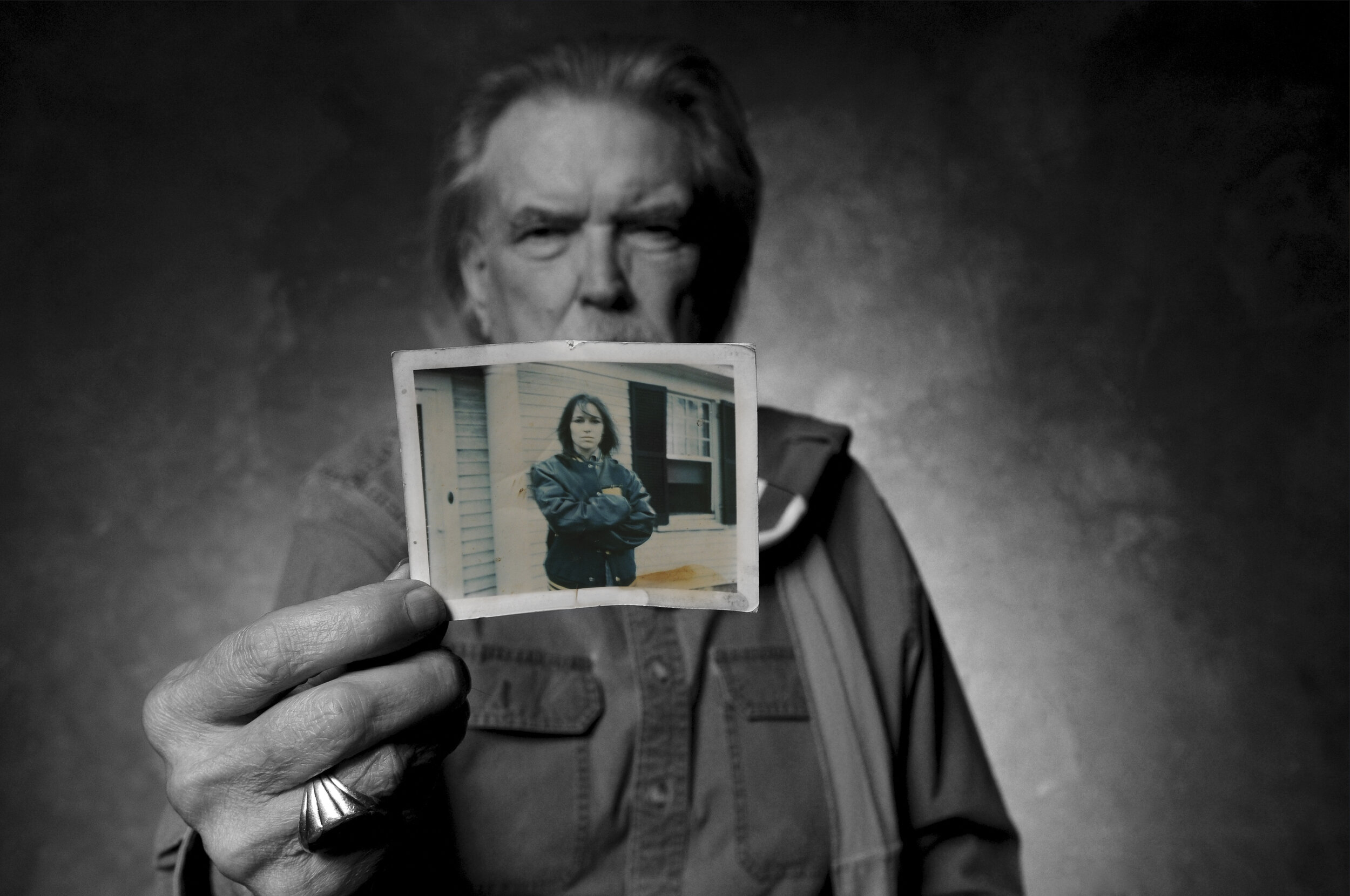

In 1996, Berry was having a conversation with his longtime friend and confidante Joe Edwards, owner of the popular St. Louis bar and restaurant Blueberry Hill. By that time, of course, Berry had done it all – performed in venues and at festivals everywhere. From a practical standpoint, there were no worlds left to conquer.

But Berry remembered his humble beginnings and was feeling nostalgic about the old days. He said to Edwards, “You know, Joe, I’d like to play a place the size of the ones I played when I first started out.”

Edwards recalls the two of them having a simultaneous flash of recognition: “Let’s do it at Blueberry Hill,” they decided.

As luck would have it, Edwards was at the time constructing the perfect venue for such an endeavor. He had purchased the bar next door to Blueberry Hill – a place called Cicero’s, which in its heyday had a primitive basement/performance space noted for birthing the city’s alternative-country scene of the 1980s-‘90s (Uncle Tupelo, the Bottle Rockets). Edwards somehow lowered in a backhoe and dug out the floor, allowing for the installation of a sizable stage, a first-rate sound system and a dressing room – accoutrements the previous establishment, though beloved, sorely lacked.

Edwards named the venue in Berry’s honor, christening it the Duck Room, after Chuck’s signature onstage move, the duck walk. He decorated it with all manner of duck-related paraphernalia – decoys and such – as well as photos of Berry and other kinds of nostalgic material – framed comic books, etc.

Because Edwards was a trusted friend like no other, Berry eschewed his regular practice of playing and being paid according to strict contractual stipulations. Instead, the pair operated on a handshake deal. At the time, however, neither of them could have guessed that their partnership would lead to a series of 209 performances – scheduled monthly, more or less – that took place over the course of 17 and a half years.

A number of factors made each of those shows special, not least of which was the sheer intimacy of the room. The Duck Room’s capacity is 340. Where else could you see rock and roll royalty in such an up-close-and-personal environment? The shows became a perennial sellout, and though local fans may have had the edge on scoring precious tickets, Berry fans from around the world managed to check a Duck Room show off of their bucket list.

Among them were a number of famous faces: the Band’s Robbie Robertson, Motorhead’s Lemmy, Lorde, rapper (and fellow St. Louisan) Nelly, My Morning Jacket’s Jim James, and broadcaster Bob Costas all witnessed Duck Room shows.

Sometimes stars even sat in: Johnny Rivers, Aerosmith’s Joe Perry, and David Bowie guitarist Earl Slick, among others. Guitarist Billy Peek, who played with Berry before joining Rod Stewart’s band, returned to the fold, as did Chuck’s original musical compatriot, legendary pianist Johnnie Johnson, who took the stage with him one last time in 2004.

For the Duck Room shows, Berry assembled a band from the cream of local players and even members of his own family. The group evolved over time, but eventually settled into what became known as the “Blueberry Hill Band”: his son Charles Berry, Jr., on guitar, daughter Ingrid Berry on harmonica, pianist Robert Lohr, bassist Jimmy Marsala, and drummer Keith Robinson.

Unlike the pickup bands on the road, Berry could count on these musicians month in and month out; they knew his physical cues and his tendency to follow wherever the spirit led him. In the free and spontaneous atmosphere of the Duck Room, Berry was known to switch tempos or even songs on the spur of the moment. He’d stop a show to recite a favorite poem. Anything to entertain.

“Live at Blueberry Hill” makes plain the comfort and freedom Berry felt playing on his home turf in these wonderfully loose and spontaneous performances culled from the Duck Room shows taking place between July 2005 and January 2006. Like most of his shows, it’s packed with the classics fans came to hear: “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Nadine,” and, of course, “Johnny B. Goode.” But Chuck also tears it up on “Let It Rock,” with daughter Ingrid showcasing on harmonica. “Carol”/“Little Queenie” offers one of those moments when Chuck starts in one place and ends up in another, all the while making it clear that it was obviously the right thing to do. There’s a full-tilt take on “Around and Around”; “Bio,” a rollicking blues on which Chuck tells his own story as only he can; and “Mean Old World,” a classic slow blues the showed how even the Father of Rock and Roll could acknowledge his forebears.

If you were lucky enough to attend one of the 209 magical Duck Room shows, you know what all the fuss here is about. If you weren’t, “Live at Blueberry Hill” at long last gives you a taste of what it was like to experience an unforgettable night in the presence of a rock and roll legend among legends.